Papers, Please is a game where you play the role of an immigration officer. A migrant walks up to your booth, you inspect their documents for any discrepancies, and you then decide whether to approve them for entry, deny them entry, or have them detained by the guards. The game is essentially a simulator for one of the more mundane jobs we can imagine having, so why play it? In order to understand how this game constitutes as play, we will see how it relates to the characteristics of play detailed by Johan Huizinga in his article, Nature and Significance of Play as a Cultural Phenomena [1].

One of the characteristics described by Huizinga that most prominently describes Papers, Please is that play is not non-serious. The seriousness of Papers, Please comes from the difficult decisions that players are forced to make. Will the player reject a migrant who is seeking asylum simply because they didn’t arrive one day earlier? Will the last of their savings go towards feeding their family, paying for heating, or buying their sick son’s medicine? These options, were they real-life decisions, would undoubtedly put the player under serious stress, so why is it that people still play and even enjoy Papers, Please? Two other characteristics described by Huizinga, play is not real and it is secluded and limited, help to explain this.

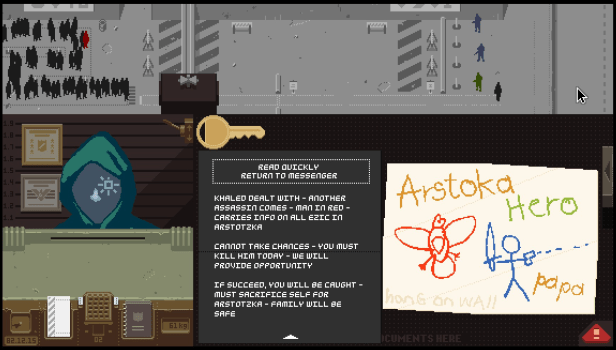

The knowledge that our decisions have no real-world impact allows us to be less critical and more risky with our decision making. It gives us the freedom of acting uncharacteristically of how we would normally act. The image above shows a member of the Ezic revolutionary group meeting with the player. They ask the player to sacrifice their life and kill the migrant denoted in red because they are an enemy of the organization. When I arrived at this scenario, I agreed without a second thought because I chose to be loyal to the Ezic. Had I been presented with this decision in real life, I would undoubtedly be more thorough in weighing the pros and cons of my decision. I’d probably spend much of that time contemplating how my choices in life led me to that situation. But Papers, Please is a game and because it is a game it is secluded, limited, and not real. I can turn away from the screen at any point and none of the consequences of my decisions will stay with me.

Huizinga states that we play because play is fun, so what exactly is fun about Papers, Please? Well it can be a variety of things including the many possible outcomes of the game, the effects of the player’s decisions, the desire to be as efficient as possible, the ability to be someone you are not, the feeling of power one has when deciding the migrant’s fate. All of these things, and likely some others, can be what makes Papers, Please such an enjoyable game despite how mundane and dis-interesting it may seem at face value.

Sources:

[1] “Nature and Significance of Play as a Cultural Phenomena.” Homo Ludens, by Johan Huizinga, 1938, pp. 95–120.